[liveblog][bkc] Aaron Perzanowski: The End of Ownership

I’m at a Berkman Klein Center lunchtime talk. Aaron Perzanowski is talking about “The End of Ownership,” the topic of his new book of the same name, written with Jason Schultz. Aaron is a law professor at Case Western Reserve Law School.

|

NOTE: Live-blogging. Getting things wrong. Missing points. Omitting key information. Introducing artificial choppiness. Over-emphasizing small matters. Paraphrasing badly. Not running a spellpchecker. Mangling other people’s ideas and words. You are warned, people. |

Normally we consumers take for granted rights for physical goods that come from the principle of exhaustion: when you sell something, you exhaust your rights to control it. That’s why we have used book stores and eBay and we can lend a novel to a friend. In this way, the copyright system gives end users a reason to participate: if you buy it, you can do what you want with it.

Online we use familiar forms of ownership: buy, rent, gift. This means that consumers don’t have to figure out every purchase from scratch; we have the basic understanding. Or do we?

The book talks about the erosion of the concept of exhaustion and the rights that flow from it.

First, copies themselves are disappearing. We used to own a copy. Now we subscribe to content streaming from the cloud. Copies are no longer rare, valuable, persistent.

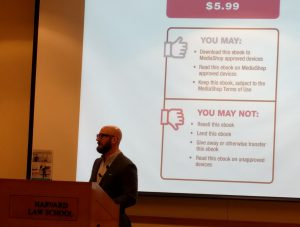

Second, courts have redefined who counts as an owner. It used to be that if you paid money for it, and you paid for it once (i.e., not a subscription), then you owned it. In 1908, the courts decided that Bobbs Merrill couldn’t control the price for which a purchased copy could be re-sold. Now, end user license agreements routinely say that you have not bought a copy and thus you can not re-sell it.

He contrasts two cases from the 9th District Court of Appeal that were decided back to back on the same day, and that are totally inconsistent. In the first case, a promotional copy of a CD had stamped on it that accepting the CD binds the recipient to a prohibition on transferring it to someone else. The court said that you can’t impose ongoing obligations that travel around with the disk.

“We’ve passed the logical breaking point…”In the same case, on the same day, the same panel considered who owns the CD in the AutoCAD package. It contained the same sort of license. The court decided that those disks were licensed by users, not owned.

Q: The music CD was unsolicited. But I bought the AutoCAD disk.

A: Do you have more or less ownership interest in something you got for free or something you paid $8,000 for?

Early in the software industry, it wasn’t certain that sw could be patented or protected by copyright, so licenses played a bigger role. But now sw is everywhere, not just on little disks. Which bring us to Digital Rights Management (DRM). At first it was at least somewhat related to protecting IP. But we’ve passed the logical breaking point, E.g., Lexmark doesn’t want people to refill their printer ink cartridges. So they had code on their printers that detected non-Lexmark cartridges or refills and wouldn’t use them. The courts disagreed.

Apple recently got a patent on using infrared light recording to disable recording on your iPhone. If a concert broadcasts this light, your phone won’t be able to record it. Or if you’re a police officer who doesn’t want to be recorded. This is an example of how tech can turn the devices you think you own against you.

“The Internet of Things is really the Internet of Things you don’t own.”The Internet of Things is really the Internet of Things you don’t own. John Deer tractors have sw embedded in them that is licensed to the owner of the tractor. GM says the same thing about cars. Another example of “machine mutiny”: Keurig.

The final problem: The deceptive “Buy Now” button. You’re usually not really buying anything. E.g., remember when Amazon deleted copies of 1984 from Kindles? “What rights do people think they have when they ‘buy now.'” Aaron and Jason did an experiment that showed that if people bought through a “by now” button, they thought they have the right to keep, device, lend, and give their copy. People make this mistake because they port over their real-world understanding of buying goods.

Q&A

Q: How does this work internationally?

A: An international exhaustion regime could have dramatic consequences for people in less developed economies. I worry about this, but I don’t know the answer. It’s very tough to generalize.

Q: How does consumer understanding of this affect pricing?

A: We tested this. Would consumers behave differently if they knew the truth? We asked how much more people would be willing to pay. It was worth about $3 more for those rights, although we didn’t ask them to actually pay that money. [Amazon lets you stream a video for 24 hrs for $3-$5 or buy for somewhere around $15, or so I recall.]

Q: How are the demographics in their understanding of the rights they’re buying?

A: Generally white men 30+ were the least accurate. They assumed they were entitled to all the rights.

Q: How are the streaming services doing in terms of the confusion?

A: We haven’t researched it specifically but my intuition is that people aren’t as confused. They know that if they don’t pay their Spotify bill, they won’t have the service next month.

A: Disney will never again release Song of the South because it’s embarrassing. The loss of a cultural object like this is very disturbing.

Q: Is people’s sense of fairness shifting so we won’t be bothered by, say, GM turning off your car’s software?

A: This is a problem with dealing with consumer expectations. We’re advocating for one set, but they’re going in the other direction. We’ve situated our argument in the language of property because it’s incredibly powerful. That’s how sw owners argue their cases: “We own this property, so we get to say how it’s used.” But the property rights of IP holders shares a border with the stuff that we as consumers own.

Q: What can be done to change the trajectory?

A: The parallels to the privacy world are instructive. The people we surveyed took these concerns about ownership to heart in a way that they don’t in the privacy context.

A: You’ve only touched the tip of the ice berg. The problem is worse than you’ve indicated.

Yes, there is a broader problem.

A: [me] Take away the deception about “Buy” buttons and one could argue that customers simply have (or will have) more options. Does your focus on the property argument misses the cultural damage that unbundling licenses will wreak?

Q: This is why we talk about exhaustion. We’re trying to explain to people why ownership matters to culture. It’;s risky to argue that we just need to correct the misinformation. But there’s some hope. The only sector of the music market growing faster than Spotify et al. is vinyl. It’s a smaller percent of the market, but there are people who will pay a price premium for something that’s tangible and that’s theirs. Likewise, physical books haven’t gone away the way people [er, like me] predicted.

If it turns out that we as a culture don’t value these objects, that we want to pay $9.99 for access to everything, there’s not a lot that I can do other than point out the virtue of this other path.

Q: Are you identifying values connected to our ownership of tangible items that we ought to be defending as we move to digital items?

A: “Property functions as a stand-in for individual freedom.”Property functions as a stand-in for individual freedom. It gives individuals the right to make choices without asking anyone for permission. Thirty years ago, you could repair your car without asking anyone for permission.

Q: Have there been court cases about medical devices?

A: Not that I know of. But we give some examples in the book where individual users want to improve their functional. Manufacturers don’t want to let users monkey with them. Car companies say the same thing.