June 1, 2014

Oculus Riiiiiiiiiift

At the Tel Aviv headquarters of the Center for Educational Technology, an NGO I’m very fond of because of its simultaneous dedication to improving education and its embrace of innovative technology, I got to try an Oculus Rift.

They put me on a virtual roller coaster. My real knees went weak.

Holy smokes.

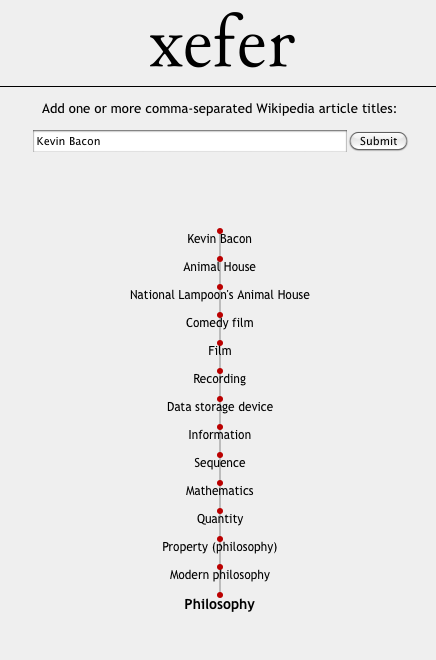

Earlier, I gave a talk at the Israeli Wikimedia conference. I was reminded — not that I actually need reminding — how much I like being around Wikipedians. And what an improbable work of art is Wikipedia.